Did you know that there are more atoms in an apple than there are stars in the universe? Isn’t it crazy how something that appears whole is made up of lots of tiny particles? Pretty mental if you ask me. When I start to think about how many particles are on an apple tree or even an apple orchard, my head starts to hurt. Never mind how many in the universe (atoms not apples). But also it is nice to think that we’re all made up of the same few fundamental particles, albeit in slightly different arrangements. A few protons, neutrons and electrons build up most of the world. And you can make alarmingly different recipes from just these three ingredients.

Now, as an observational astronomer, usually when I stumble onto a web page related to particle physics, I immediately go back one page, delete the cache and history and consider throwing my hard disk into the ocean in case my browser remembers the web address and ever accidentally takes me back there again. However something very interesting has been happening in the world of particle physics that’s intrigued me. During my usual scrolling of the ADS (Astrophysics Data System) abstract service, I noticed a few papers have been making waves recently.

All contain the title with something along the lines of; “W-Boson Mass Anomaly Offers Clues to the Nature of Dark Matter”, "W-Boson Struggles with Weight Gain: Can They Bounce Back?", “Exclusive; W-Boson spills the beans on Harry and Meghan”.

Okay I may have made these up, but the actual titles are very boring.

The Subatomic Scoop, April 2022.

The Subatomic Scoop, April 2022.

What’s happened is that an elementary particle called the W-Boson has been measured with a mass larger than is theoretically predicted in the Standard Model (this is the model that describes all the known elementary particles). And this is having a big impact on particle physics as a whole.

How does this relate to astronomy? Particle physics and astrophysics are linked. Obviously understanding particles and how matter is formed, helps us understand all the strange things going on in the Universe. Particularly it may give us answers to some big question marks like dark matter and dark energy.

Well in the next couple of articles, I’m going to dive into particle physics and try and explain to the best of my ability what’s going on with this W-Boson and why it’s making noise. It’s not boring I promise! Please keep reading.

This first post is going over some background info on the Standard Model.

The Standard Model

First things first, we need to revise some Higher physics. If I take myself back to my school days, I vaguely remember this thing called the Weak force. If you’ve not taken physics, the Weak force is one of the 4 fundamental forces in the universe. Earth, Wind, Fire and the Weak force. Funnily enough, that’s also the name of a band who had a flop called November.

Of course I’m joking. The four forces of the universe are Strong force, Weak force, the Gravity force and the Electromagnetic force. These are the only forces we have! Isn’t that crazy. The whole universe only has these 4 to make up it’s complexity. More recently physicists have been trying to make a unified theory of all the forces. So far they’ve combined the Weak force and the Electromagnetic force into the “Electroweak Force”, but for this article I'm going to keep them separate. The Gravity force and Electromagnetic force are perhaps a bit more intuitive, Gravity is the force that keeps us on the ground, and Electromagnetism is the force between electric charges - e.g current passing through a wire. The Weak and Strong force are maybe more difficult to comprehend. These forces only interact over very short distances between subatomic particles.

Subatomic particles

Subatomic, aka particles inside of an atom. You will know electrons, protons and neutrons, but there’s even smaller particles called quarks which are the fundamental particles that make up the protons and neutrons.

We can think of quarks as different types of ice cream flavours that you can add together to make another different type of ice cream. For example, a scoop of vanilla, strawberry and chocolate make neapolitan. Or you could have 2 scoops of vanilla and 1 of raspberry for a raspberry ripple. Or a scoop each of chocolate, marshmallow and pecan ice cream to make a RockyRoad.

New type of particle recently discovered. Credit.

New type of particle recently discovered. Credit.

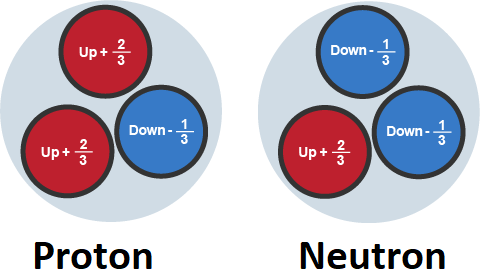

A proton is made up of 3 quarks, 2 scoops of UP, and 1 scoop of DOWN. I know these flavours don’t sound very tasty, but particle physicists are a weird group. These flavours mix together to give a proton an overall positive charge, which balances out the negative charge of an electron in an atom. On the other hand a neutron is made up of 1 scoop of UP and 2 scoops of DOWN, which ends up giving the particle a neutral charge (DOWN flavour is a bit bland and not as strong as the UP).

If you’d like to do more of a deep dive into quarks and what they are and learn more about their flavours, here’s a great article.

Proton is made up of 2 up quarks and 1 down quark. Neutron is made up of 1 up quark and 2 down quarks. At this point I would like to give thanks to BBC bitesize, who have given me 90% of the information and images I’m using here.

Proton is made up of 2 up quarks and 1 down quark. Neutron is made up of 1 up quark and 2 down quarks. At this point I would like to give thanks to BBC bitesize, who have given me 90% of the information and images I’m using here.

Strong and Weak force

After a quick crash course in the subatomic particles we can go over the Strong and Weak force in more detail.

The strong force is the force that holds quarks together in a proton or neutron, and further holds protons and neutrons in the nucleus. Protons have positive charge, so naturally want to repel each other, but the Strong force holds them together. Think of it like the glue that holds all the small particles together. Very important if we’re going to build atoms and eventually larger molecules! As such it is responsible for the underlying stability of matter.

Actual image of the strong force keeping a nucleus together.

Actual image of the strong force keeping a nucleus together.

The Weak force is weaker than the Strong force (go figure). And it is even more short range and only interacts between quarks. It can change one flavour of quark into another.

Stretching my analogy to it’s limits, the Weak force is like a rude icecream server who can change a scoop of your icecream order to a different flavour! How rude. This means that while you’re tucking into a delicious proton, they suddenly change one of the UP scoops to a DOWN scoop and all of a sudden you’re taking a bite into a neutron - not what you ordered at all. 0/10 on tripadvisor. Would not recommend.

Here’s the sadist that changed my proton order. Credit

Here’s the sadist that changed my proton order. Credit

Now, while annoying in my analogy, the Weak force is very important in real life. It helps keep the right balance of protons and neutrons in a nucleus. The weak force is very important in the nuclear fusion that happens in the sun, as it causes a proton to change into a neutron (a reaction called Beta decay) and hence new hydrogen isotopes are able to form.

What is making these forces “happen”? How is a proton just magically turning into a neutron? How are protons and neutrons being stuck together in a nucleus? What’s causing these forces!? Patience, young grasshopper, there is still much to learn.

Bosons

The answer is bosons! So it turns out there are other types of particles that give rise to the four fundamental forces and they’re different from the particles that make up matter. In fact we can put particles into two groups.

- fermions – the particles which make up matter (quarks, protons, electrons etc)

- bosons – the particles which give rise to forces

| Force | Boson |

|---|---|

| Electromagnetism | Photon |

| Gravity | Graviton ? |

| Strong Force | Gluon |

| Weak Force | W and Z |

So Photon, Graviton, Gluon and W and Z! These are all bosons! And they carry the force. You can see a little question mark next to Graviton because scientists haven’t been able to find this boson yet, it’s only theoretical.

The Weak Force has 2 bosons, W and Z. The W boson can have either a positive or negative electric charge. The Z boson is electrically neutral (zero charge.. hence the Z).

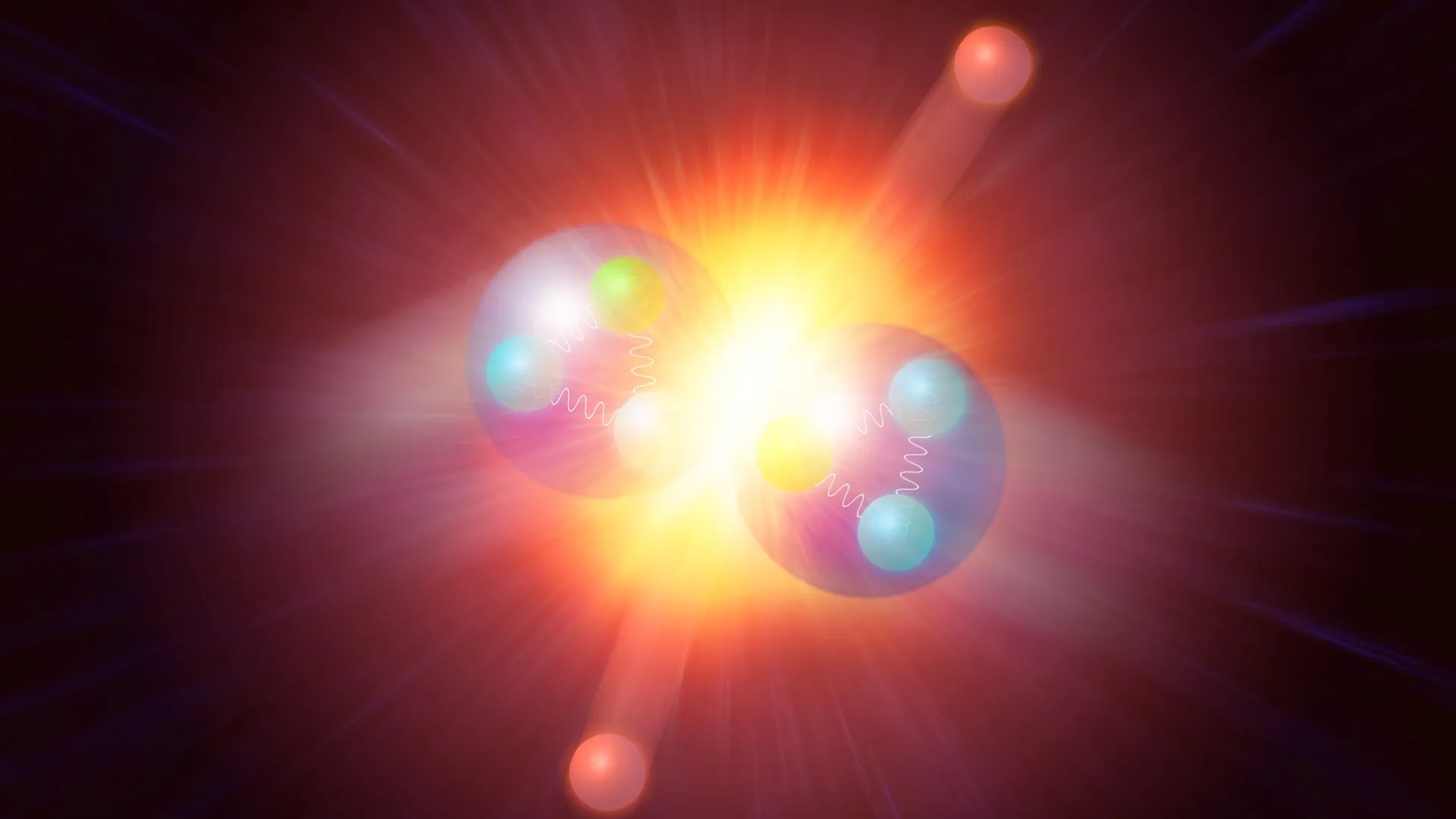

If you were alive in 2012, you might remember the name Higgs boson that a lot of people were making a fuss about. The Large Hadron Collider smashed some particles together and found this boson which at the time was only theoretical. Well this is the 5th boson. The Higgs isn’t a force-carrying boson, like the other four, but is a boson that gives mass to other fundamental particles.

An illustration of two bosons produced by two colliding protons. (Image credit: Mark Garlick/Getty Images)

An illustration of two bosons produced by two colliding protons. (Image credit: Mark Garlick/Getty Images)

Note: there’s a lot more to learn about fermions, bosons and different types of elementary particles. But we’re sort of doing a bare minimum crash course here. Check out the links at the bottom of the page to dive deeper.

How to weigh a W boson?

After the Higgs boson was discovered, scientists could predict the mass of the W boson more precisely. Using the Higgs Boson mass, a few other measurements and a formula from the Standard Model, you get a very accurate prediction of the W boson mass.

But to measure the W boson mass physically is a very different matter.

W bosons have a very short life span sadly, and are too short-lived to be seen directly, so scientists study them by observing the particles they break into when they decay. By measuring the energy and path of these secondary particles, scientists can determine the mass of the W boson using laws of energy and momentum conservation.

This is what the CDF (The Collider Detector at Fermilab) collaboration did when they found that the mass of the W boson was slightly larger from the predicted theoretical mass in the Standard Model.

As well as being different from the theoretical model, the recent CDF result is also slightly different from other experimental groups, and needs to be checked again with the Large Hadron Collider just to make sure.

However, if the new CDF measurement is correct, then it means something must be missing from the Standard Model theory and there is new physics that is yet to be uncovered….

DUN DUN DUN

Stay tuned for part 2 of this deep dive into particle physics!

References

BBC Bitesize: The Standard Model

New Scientist: Strong Nuclear Force

Britannica: Strong Force

Energy Education: Weak Nuclear Force

Hyperphysics: Fundamental Forces

Symmetry Magazine: What's up with the W-boson mass?

Space: What are bosons?