Happy International Women’s Day!

As a woman myself, International Women’s Day is one of my favourite day’s of the year (the 1st is pancake day obviously) because we get to appreciate all the wonderful women in our lives and reflect on the achievements of others. Women take up about 1 in 5 of roles in the space sector, but luckily this number is increasing! The number of women in astronomy has doubled in the last decade, and among young astronomers, about one in three are women.

Despite us only making up a third of the field, receiving discrimination and also having fewer opportunities, we have made great contributions to astronomy and space science. This article goes through some of the most influential and important female figures in astronomy history. I couldn’t put them all in because there’s just too many.

Remember when that headteacher of a London highschool said that girls don’t like physics because it has “hard maths”? I guess all these amazing women didn’t get the memo:

Caroline Herschel, 1750-1848

Credit: M.F. Tieleman, 1829. © The Bridgman Art Library.

Credit: M.F. Tieleman, 1829. © The Bridgman Art Library.

Caroline Herschel (from Hannover, Germany) was the first female astronomer to be paid for her work, and thus is considered the first female professional astronomer. She didn’t always want to be one, however. She started off her career as a musician and soprano vocalist. Her older brother, William Herschel, was a musician and she would give performances at his concerts. But, William decided he wanted to move away from music and become an astronomer, and being very close to her older brother, she decided to support him. Through this collaboration and being his assistant, she became a significant astronomer in her own right.

Caroline helped make observations and calculations towards her brother's work. Together they made a catalogue of a 20 year survey of the night sky including 2,500 nebulae and star clusters. This was before we had computers, so this was done all by hand and a lot of note-taking and organised paperwork! The finished work was called the New General Catalogue. If you know any deep space objects with a weird name like NGC 1976, know that the NGC part originated from Caroline and William Herschel’s work!

She didn’t have a lot of time to do her own research, but even so she discovered 14 new nebulae and was the first woman to discover a comet. She continued to discover 7 more comets throughout her career.

Because of the importance of her work and respect as a scientist, the crown started paying her £50 a year as William’s assistant. This was at a time when it was rare even for men to receive a salary for science endeavours. Caroline became the first woman in the UK to earn an income as a scientist, as well as the first woman ever to receive one in the discipline of astronomy.

Mary Somerville, 1780 - 1872

Credit: New Scientist

Credit: New Scientist

Mary Somerville was a Scottish (woo!) scientist and mathematician from Jedburgh. Scots may recognise her face from the £10 note.

Like Caroline and other women during her time, Mary wasn’t allowed to attend any prestigious school of science. It was only through her family's wealth and connections that she was able to become educated.

Mary was an avid learner during her childhood and loved reading books, particularly about mathematics and physics. However, in her mid-twenties she married, let’s say, a not-so-supportive husband. Here’s a quote from her:

“Although my husband did not prevent me from studying, I met with no sympathy whatever from him, as he had a very low opinion of the capacity of my sex.”

Luckily (for her) her husband died, and she was left with an inheritance to support her intellectual curiosities. The dream. She dived head first into her studies and strung up the courage to partake in several puzzles published by mathematical journals. She began making a name for herself from her solutions. After her 2nd marriage to a very supportive husband, Dr William Somerville (we approve), they moved to London and became very well-connected with other prominent scientists, writers and artists. At the age of 46, she published her first scientific paper on magnetism and the solar spectrum.

Her two most famous works are Mechanism of the Heavens (1831) , which is a translation of 5 volumes of gravitational mathematics by the french mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace. In her own words she "translated Laplace's work from algebra into common language". The textbook was used in Cambridge for undergraduates until the 1880s.

Her second famous work is On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences (1834) , and was one of the best-selling science books of the 19th century.

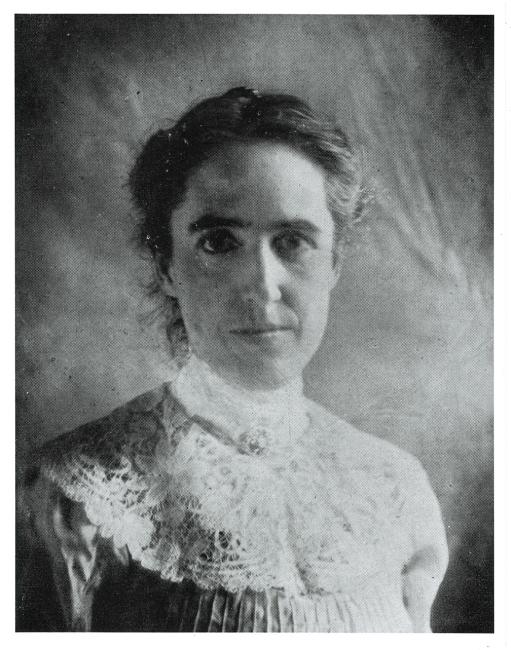

Henrietta Swan Leavitt, 1868 - 1921

Credit: SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Credit: SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Henrietta Swan Leavitt was an American astronomer, most famous for characterising Cepheids, a type of star whose luminosity fluctuates - a variable star.

She graduated from Radcliffe College in Massachusetts and started working at Harvard University as a human computer. Her task was to measure and catalog the positions and brightness of stars. She did this by using the observatory’s photographic plate, as women weren’t allowed to handle telescopes (!). I guess we were too feminine or too stupid to handle a telescope? Not sure the reasoning behind this.

After studying thousands of variable stars in the Magellanic Clouds, she discovered that there was a link between the fluctuation period and the luminosity of a star. This means that if we measure the pulsation time of one of these stars, we can calculate it’s true brightness. By knowing the true brightness and comparing it to the apparent brightness seen from Earth, we can determine the distance to the star. The period–luminosity relationship for Cepheids is now known as "Leavitt's law".

This ground-breaking discovery allowed scientists to estimate distances to other galaxies and faraway objects and paved the way for modern astronomy's understanding of the structure and scale of the universe. Before this discovery, there were debates about whether the milky way was the only galaxy and whether our sun was the center of the universe.

Unfortunately, Leavitt didn’t get a lot of acknowledgment for her work, as the credit mostly went to the director of the observatory Harlow Shapley. However, since her death, other astronomers have recognised her importance. Edwin Hubble used Leavitt’s work to help him compute the distance to the Andromeda Galaxy - the closest galaxy to Earth. Hubble often said that Leavitt deserved the Nobel Prize for her work.

Vera Rubin, 1928 – 2016

Photo credit: AIP Emilio Segre Visual Archives, Rubin Collection.

Photo credit: AIP Emilio Segre Visual Archives, Rubin Collection.

Vera Rubin! The mother of Dark Matter. Vera Rubin may be my favourite astronomer since she was revolutionary in discovering the existence of dark matter! Even with this whopping discovery, she never got a Nobel Prize, which many think was snubbed due to her sex.

Rubin studied her PhD at Georgetown University in Washingtom D.C, which she started when she was 23, pregnant and with a child at home. Her PhD thesis concluded that galaxies were clumped together, and not randomly spread out throughout the universe - a controversial idea at the time.

After teaching for a few years at Georgetown, she took a research position at the Carnegie Institution in Washington, where she teamed up with astronomer Kent Ford. Her work focused on observations of the dynamics of galaxies.

In the 70's, when Rubin and Ford began to study the rotational speeds in the Andromeda galaxy, they discovered something very weird. Stars on the outer regions of the galaxy were travelling just as fast as those near the center. This was odd, because Andromeda didn’t have enough gravity to hold onto stars traveling that fast, the outer stars should have been flung into space a long time ago. Her calculations showed that galaxies must have 10 times as much matter as can be accounted for by the visible stars!

Rubin wasn’t the first scientist to come up with the idea of dark matter, that belongs to Swiss astronomer Fritz Zwicky who in 1933 (more than 40 years before) published a paper on the Coma Cluster, describing how there wasn’t enough gravity to keep this cluster together and there must be some sort of “dark matter” there we can’t see. Unfortunately, his peers thought that was a ridiculous idea and not much happened after that - until Rubin. Rubin fortified Zwicky’s theory, and found evidence of dark matter in many more galaxies. She helped show that 80% of matter in our universe is made of dark matter.

As for her never receiving a Nobel Prize, I will leave you with this quote from astronomer Emily Levesque.

“The existence of dark matter has utterly revolutionized our concept of the universe and our entire field; the ongoing effort to understand the role of dark matter has basically spawned entire subfields within astrophysics and particle physics at this point. Alfred Nobel’s will describes the physics prize as recognizing ‘the most important discovery’ within the field of physics. If dark matter doesn’t fit that description, I don’t know what does.”

Like all these women on the list, Rubin received a lot of sexual discrimination during her studies and career, something which she fought against and because of which, was a strong advocate for women in science.

Jocelyn Bell Burnell, 1943 - present

Credit: BBC

Credit: BBC

I had the pleasure of seeing a lecture by Jocelyn Bell Burnell while I was studying at St Andrews University. Bell Burnell is a Northen Irish astrophysicist born in Belfast. She attended the University of Glasgow where she received a bachelor's in Physics in 1965. From there she went to study for her PhD in radio astronomy at Cambridge University.

At the time of her PhD, quasars were an exciting, new topic (only discovered in 1963). A quasar is an extremely luminous supermassive black hole in the center of a galaxy, that gives off radio emissions. While conducting research on quasars in 1967, using a radio telescope she helped build, she discovered a series of extremely regular radio pulses.

She went to her PhD advisor, Antony Hewish, who initially was very sceptic about the signal, saying it was some sort of man-made interference. But after her persistence, they spent a few months investigating the origin of the radio pulses. After using more sensitive equipment to observe, and observing radio pulses elsewhere, the team discovered that it wasn’t a quasar at all, but a star! A very heavy star called a neutron star that was spinning rapidly and producing these regular patterns of radio waves. Later to be called pulsars.

This was a great discovery! And the paper announcing it, named Bell Burnell as second author. In 1974, the Nobel Prize in Physics was given to Hewish and Martin Ryle for the discovery of pulsars. Noticeably, even though Burnell was the first person to discover a pulsar, she was omitted from the prize (are we seeing a pattern here?).

Jocelyn Bell Burnell went on to teach and become a professor at a few universities including; the University of Southampton, University College London, Royal Observatory, and the Open University.

Bell Burnell is an advocate for women in science. In 2018 she donated prize money to help women, under-represented ethnic minorities and refugees pursue careers as physics researchers.

Barbara A. Williams, 19?? - present

Credit: Scott Williams via Astronomers of the African Diaspora

Credit: Scott Williams via Astronomers of the African Diaspora

Barbara A Williams was the first black women to receive a PhD in astronomy in 1983. After receiving her bachelors in physics, she moved to the University of Maryland to become a graduate student. Her research was specialized in radio astronomy, in particular looking at small groups of galaxies.

Her publications include the studies of the observations of neutral hydrogen in elliptical galaxies, the IC 698 group of galaxies and other galactic systems and interstellar gas. Neutral hydrogen is prominent in gas clouds in the space between stars and other objects (the interstellar medium). By mapping neutral hydrogen emissions with a radio telescope, we see the detail and structure of galaxies. Also when two galaxies collide, we can use this feature to determine which way the galaxies are moving

Not a lot else is known about Williams, but she paved the way for other black women to enter the astronomy field.

Jane Luu, 1963 - present

Credit: University of Oslo

Credit: University of Oslo

Jane Luu is a Vietnamese-American astronomer. Luu arrived to the United States with her family as a refugee when Saigon fell in 1975. They lived in motels and refugee camps before settling in Kentucky. Luu received her bachelors in physics in 1984, and then worked at NASA where she decided she wanted to pursue a career in astronomy.

Afterwards she became a graduate student at the University of California Berkely, working with astronomer David C. Jewitt, where they made an important discovery about our solar system.

After the discovery of Pluto in 1930, many astronomers suspected there might be more further a field. Scientists hypothesized a “Kupier Belt”, with lots of small objects and material on the outskirts of the solar system. Luu and Jewitt spent five years searching for such possible objects. Finally, in 1992, they were rewarded when they discovered 15760 Albion! The first object discovered in the Kupier Belt, measuring about 125 kilometres in diameter. Since then more than 2000 further objects have been found beyond Neptune.

After receiving her doctorate, Luu worked as an assistant professor at Harvard University. She was also a professor at Leiden University in the Netherlands. She has received the Kavli Prize and the Shaw Prize for her discoveries and contributions towards our solar system.

In the future

Safe to say we have come along way from the times of Caroline Herschel. But although strides have been made for women in STEM, there’s still some work to do. Physics and astronomy fields have a good number of girls studying in school and university, but staff faculty numbers remain a problem. Also engineering still has a big discrepancy between women and men. Lastly ethnic minorities remain under-represented in physics and astronomy in western societies.

Here’s to the future, and for women, from all cultures and backgrounds to have better opportunities and resources in science.

References

https://www.stsci.edu/stsci/meetings/WiA/boyce.pdf https://www.aip.org/statistics/reports/women-physics-and-astronomy-2019 https://spaceskills.org/census-women#education-and-work-choices https://www.itv.com/news/2022-04-27/government-adviser-girls-dont-take-physics-as-they-dislike-hard-maths https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/10/1102082 https://www.britannica.com/biography/Caroline-Lucretia-Herschel https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/caroline-herschel https://www.space.com/17439-caroline-herschel.html https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mary-Somerville https://www.skyatnightmagazine.com/space-science/mary-somerville-scottish-scientist-life/ https://www.space.com/trailblazing-women-in-astronomy-astrophysics https://www.amnh.org/learn-teach/curriculum-collections/cosmic-horizons-book/vera-rubin-dark-matter https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jocelyn-Bell-Burnell https://astronomy.com/news/2016/10/vera-rubin https://astrobites.org/2020/06/20/1981-barbara-williams-becomes-the-first-black-woman-to-get-a-phd/ http://theskyisnotthelimit.org/scoping-out-radio-astronomy/2021/02/08/the-first-black-woman-phd-astronomer-barbara-a-williams https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jane-Luu